- Home

- Luke Palmer

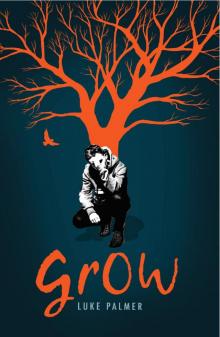

Grow Page 2

Grow Read online

Page 2

The cats didn’t seem to care what you called them. They never responded to any names.

*

The radio DJs’ change-over at 7 o’clock wakes me up. They howl with laughter at something that one of them has said and I come to with a jolt. I’m sat in the only pool of light in the house, having fallen asleep mid-question, my hand scrawling a smooth arc across the page. I scrabble the books together, stuffing them back in my backpack. In my bleary rush I knock over my mug, the last dregs of tea spilling onto a couple of letters from this morning. Almost instantaneously, I hear Mum’s keys in the lock, the rustle of shopping bags coming through the door. I grab some kitchen towel and mop up.

Mum enters with a loud sigh of accomplishment. She’s always more cheerful after she’s done the shopping, wearing the achievement like a badge as she unpacks food into cupboards and drawers, arranges the fridge with the older stuff at the front.

‘Hello, love,’ she says, beaming at me and the shopping all at once. ‘Good day?’

I wonder (but don’t ask) why she still goes shopping every week. We must throw away most of the stuff she buys. We’ve got at least six tins of kidney beans in the cupboard, probably a dozen of chopped tomatoes. I found a bag of peppers at the bottom of the fridge a few weeks ago, unopened. The contents were almost completely liquid – you could only tell what they used to be from the picture on the packaging. And there are potatoes in the vegetable cupboard that have sprouted long, white tendrils, reaching towards the light like tiny hands and arms.

‘Fine,’ I reply, taking my bag into the hallway. ‘Nothing to report.’

She ruffles my hair as I pass her, and maybe thinks about doing the thing with her hand on my cheek again, then doesn’t. ‘There’s another two bags in the boot,’ comes her voice from the kitchen, warm, homely, comforting. But I know this, and I’m already halfway down the driveway. Every week it’s the same number of bags, the same things in each one. And, when Mum’s having a good week, the same schedule of meals each night.

Just the same as when Dad was alive.

But hey, it is what it is.

SIX

It is what it is.

It was a line in a TV series that Mum and I watched together a while back. We’d started watching it after the accident, during the time when I didn’t go to school, Mum didn’t go to work and we would shut the curtains and not move all day. I call it the The Drowned Time.

We’d kept watching that show, episode by episode, through the time when the phone calls and the visits from journalists had become almost unbearable; through the time when the phone calls and visits were from people checking that I was being looked after properly. It was a long-running show, loads of series, and we were thankful for it.

Whenever the characters in this TV series were talking about the situation being really bad – which it often was – they’d look at each other and say, ‘It is what it is’. It became our mantra for a while. We’d kept watching after we re-surfaced from The Drowned Time. And we still watch it now, when we need it. We’ve started again from the beginning, episode after episode. The mantra still makes us smile.

‘It is what it is’ sums things up nicely. It’s definitely not good, but it’s not bad enough to make you stop and want to lie down and never get up again. At least not anymore it isn’t. It’s a situation that you have to deal with, even though you’d rather not, and everyone accepts that it’s crap and does the best they can.

It is what it is.

*

This evening, after chips and chicken Kiev – ‘brown dinner’, Mum calls it (we always have brown dinner on big-shop day) we’re watching one of Mum’s property shows on catch-up.

‘I don’t get this, Mum. So, there’s a couple looking to move house who need to look at houses, and they get shown some houses by some people who are really good at looking at houses. Why can’t they do it for themselves?’

‘I don’t know, smartarse. It is what it is!’ Her mood hasn’t gone down again since we unpacked the shopping. ‘It’s my escapism.’

‘You should just go and have a nose around next door every now and again. Wait until they’re out. I’ll call you if they come home.’

She hits me with a cushion. We’re both smiling. One of the professional house-lookers is talking to the couple about ‘outdoor space’. ‘Isn’t that all there is outdoors? Space?’ Mum says.

The couple are standing in a green square at the back of the house they’re looking at. It’s astroturf, like I used to train on every Wednesday evening with the football team up at the school. Mum scoffs, ‘I don’t understand why people are doing this nowadays. What’s wrong with grass? Why are people too busy to mow lawns or deal with mud or give worms somewhere to live?’

‘It is what it is,’ I say.

She smiles.

Evenings like this are rare now. I’ve got homework to finish – English Lit revision as well as the Maths from earlier. But these are tests I’m willing to fail.

As if reading my mind, Mum asks, ‘Homework?’

‘No, finished it all.’

‘Liar. Off with you.’ She digs her feet in sideways, under my leg, and pushes. I make to complain. ‘Hey, it is what it is,’ she says.

I throw a cushion at her on my way out.

Later, she puts her head around my door to say goodnight. ‘Thanks for your help this evening, Josh. With the shopping. We’ll watch something you want to watch tomorrow night, OK?’

I nod, knowing that tomorrow night Mum probably won’t be like this, if she’s here at all. And even if she was here and we did find something to watch that she agrees to, she’d probably fall asleep before it’s halfway through.

So I’ll go and watch things upstairs, on my own, on my laptop, the house around me so quiet I’ll think it has eaten itself.

But hey, it is what it is.

SEVEN

Breaktime. Younger kids slip past me, their too-big backpacks beating against their shoulders as they run. A group of girls is forming outside the toilets, waiting for the next group member to emerge. They’re blocking the corridor and a young teacher whose name I don’t know moves them on towards the playground doors. As soon as the teacher goes into her classroom, the girls come back, disappear into the toilet, then come out one by one and wait for each other. They do this every Friday. Every day, probably. But I’m only here to watch on a Friday.

I’m sat on a set of lockers. There’s a kind of alcove at the end of the corridor with lockers set into a bench. I’m sat on these, looking back up the corridor. I can see its whole length, which must be a hundred metres at least. It’s one of the places I go that’s surrounded by noise, but is quiet and removed. That way, people don’t notice you sitting on your own. They don’t ask questions.

I’ve got a few routes that I walk as well. It’s important, when you’re walking around school on your own, to walk like you have a purpose, and to not seem too morose. You don’t want anyone commenting or looking at you for too long. Don’t smile at everyone you see, but don’t keep your head down either. It’s a fine art. Don’t walk the same route every day; you have to mix things up so people don’t spot a pattern. And don’t go places where there’s too many teachers. There are a few places around school that I try to avoid. Mostly it’s the toilets that block up when it’s rained too much, but the staff room and the year group offices are high on the list too; that’s where people ask questions.

It’s easier that way.

When I first went back to school, there was the ‘little chat’ with Mrs Clarke, our head of year, and the counsellor, Miss Amber, who handles all the emotional issues. Normally Miss Amber deals with girls pulling each other’s hair out over the weekend or sending naked pictures of themselves to boys who then put them online. She’d looked at me as if I was a strange sea creature she’d read about but was never expecting to find.

I’d told Miss Amber and Mrs Clarke in that first meeting that I didn’t want any of the teachers to talk to me a

bout it. About Dad. And to be fair, they didn’t. But instead they just looked at me with the look – somewhere between pity and panic. It’s still there. Even from the new teachers who’ve joined since. If any of them see me in the corridor, I get a look and a smile. Or, even worse, a cheery ‘Hi Josh!’. Even from teachers who’ve never taught me and new teachers who shouldn’t know my name.

All the students do it too – the look. Even the new Year Sevens. Word soon gets around I guess.

But no one has ever actually mentioned Dad yet.

Except Mr Walters.

A few weeks after that first time, when I’d caught up with the rest of the class again and didn’t need any extra sessions after school, Mr Walters had asked me if ‘He’ was good at science at school. Somehow, I’d heard him pronounce that capital ‘H’. I’d stared back, blankly. Mr Walter’s carried on – did I get my abilities from my mother’s side of the family as well as His? I’d shrugged and said I didn’t know. Then went straight home in the middle of the day and cried.

I told Mum about it.

The next day, I’d got a note telling me to go to Miss Amber’s office at the end of school. Mum was there with Mrs Clarke, Miss Amber and Mr Walters. I froze when I saw them through the little, grilled window in the door, wanting to melt into a puddle and be mopped up before they saw me. I was too late.

But when Mrs Clarke opened the door to me, she seemed to be laughing. So did Miss Amber, and Mr Walters. And Mum.

‘Hi, love.’ Mum’s voice sounded puffed up, full of air, the way it did just before she started to cry.

Mrs Clarke showed me to a comfy seat between her and Mum. Mr Walters sat opposite, on Miss Amber’s office chair. Miss Amber stood leaning on the windowsill. It wasn’t a very big office. Mum took something out of her bag and held it on her lap.

‘Josh, I’d like to apologise,’ began Mr Walters. ‘I’m sorry that I keep mentioning your father. I know that you don’t like it, that it makes you uncomfortable. And I wanted to let you know that I didn’t want to upset you in any way, or bring up any bad memories.’ He sat leaning forward with his clasped hands between his knees, looking concerned.

‘Mr Walters was at school with your dad,’ Mum said next, definitely on the verge of tears now. She passed me what she was holding – a rolled-up piece of paper. I unrolled it. It was an old picture of Dad’s class at school. I remember him showing it to me once, years ago. We had laughed at the haircuts.

Mr Walters leaned over, pointing to a boy in the top row with short, dark hair and big-rimmed glasses. ‘That’s me,’ he said. ‘I was in your dad’s year, but we weren’t in the same classes. We weren’t close, and we didn’t keep in touch after school. When I heard about … what happened…’ He trailed off.

‘I think Mr Walters is also upset about your father, Josh.’ Mrs Clarke took over. ‘If you would like to change Biology class, then Mr Walters will not be at all put out, and nor will we. But he wanted to tell you himself that he has his reasons for thinking about your dad.’

‘You look just like him,’ said Mr Walters, weakly. This was true. In the last few months, I’d often looked at our photographs side by side on Mum’s bedside table as I’d tried to wake her with a cup of tea before leaving for school.

‘It’s fine.’ I managed a hoarse whisper. ‘It’s OK.’

Mum had actually started crying now, quietly, smiling at Mr Walters.

Mrs Clarke clapped her hands once. ‘Good, that’s settled then. Josh, Mrs Milton, thank you both for popping in. And at such short notice. I can’t imagine what a difficult…’ and it went on like this for a few minutes. I sat hunched in my coat, trying to smile, following the conversation that moved very slowly around the room like a car about to run out of petrol. Mr Walters was asking where we were living now, he said that he’d regretted not meeting up with Dad for a pint and a catch-up. It was so silly, he said, the two of them still living in the town they grew up in, and not in touch with each other.

‘And now…’ he’d faltered. ‘And now…’

All I could think about was how many pupils would be outside to watch me leaving the school with my mum, whose face was blotched and red, and who wouldn’t let go of my hand.

As we were standing to leave, Mr Walters had placed a hand gently on Mum’s elbow, then turned to me. ‘I’m truly sorry, Josh. I promise you that it won’t happen again.’

But it does.

EIGHT

I might not speak much, but I listen well. And I pick things up. All day there’s been a buzz around school about a party at Jamie’s house this evening.

Jamie and I used to be good friends, from the football team and before, but I haven’t spoken to him for a while. The excuse I used to Mum about dropping out of football was the same one I told Jamie: I wanted to ‘focus on my school work’. It worked better with Mum than with him.

I was never the best or most important player in the team, nor was I the worst, so I don’t think the team have hugely missed me. I used to enjoy playing though. I was what you’d call ‘solid’. A dependable, mid-field player who would scrap for the ball and then, normally, do something half decent with it. Not going on a run, beating three players and slotting the ball into the other team’s net, but giving it to someone who could, or sending the ball out wide, into a space I’d noticed was empty but was sure our wingback could get to. Dad used to say that there weren’t many players that could spot those passes, and that I made them more often than the rest of the team put together. I wasn’t sure about this. Dad said I should get used to being under-appreciated.

For a while I’d tried to keep playing. Mum still came along, but she didn’t shout anything anymore. I got the impression she wasn’t really watching. I realised then how much football had been a part of her life too. Watching her standing on the touchline there in the rain, staring out into the middle distance, it felt like I was drowning. The worst bit was knowing she was just trying to keep something alive for me, and that every second was killing her. When I said I was going to stop, she tried her best not to look relieved.

Jamie and I didn’t fall out, just stopped talking, and we still nod at each other in the corridors. Jamie knew that people had started treating me differently, even though he never did. We’re still in a lot of classes together, and the teachers’ habits of keeping us apart lower down the school (when we used to talk a lot) have been carried over to this year as well. Even though I don’t really speak to anyone, not anymore.

I’m sitting just behind Jamie in our English class, the test I’d revised for last night about to start, when he turns around.

‘You coming?’

‘What?’

‘Friday. Are you going to come? You’re invited.’

‘To your house?’

‘You remember where it is, right?’ Jamie smiles.

I smile back. ‘Maybe.’

And that’s it. Moment over. He goes back to his work, chatting to Louisa sitting next to him. He says something that sounds like ‘I tried’. She looks concerned.

I think about it. Mum won’t be home this evening; Fridays are when she goes to see her parents. She’s stopped insisting that I come with her ever since we’ve started GCSEs, so I’ll be on my own. And will be until Sunday morning, probably. So Mum wouldn’t have to know about this. Not that she’d have a problem at all, I just know she’d make a big fuss and say things like ‘it’s good that you’re getting out again’ or ‘will there be girls there’ or, even worse, ‘fine, I’ll just sit in on my own’.

I throw my pencil at Jamie’s shoulder. It glances off, clatters across the desk in front of him. He turns around.

‘What time?’

‘Er … after half eight?’

‘Josh. Stop talking,’ hisses Mrs Burgoyne from the front, and I’m not sure if she or Jamie is more surprised.

NINE

Since Mum hasn’t changed the shopping list for a while, we’ve got a good supply of beer in the garage, all stacked up. Dad was

the only one who drank it. There are bottles at the back that are probably off by now. I grab two four-packs from the top and replace them with a few packs of cokes a little further down so that the tower of beer stays the same height. I doubt Mum would mind if she knew I was taking them, but it saves time this way, and I don’t want to phone her at my grandparents’ house. It’s never a short conversation.

Nanna and Grandad have been really good for Mum, and are happy that I’m mostly ‘keeping out of it’ as they say. After it happened, they were coming over a lot, so much that I started calling the spare room their room. But they have lives like the rest of us, so before too long their visits got less frequent. Now Mum goes there instead whenever she feels like she needs a rest. Which is every weekend. And sometimes during the week.

She’s never mentioned moving house, but I’ve seen her browser history and I know she’d like it if we went to live near them. I think she’s just waiting until I finish school. Or this part of it, at least.

I sling a pizza in the oven while I go upstairs for a shower, stuffing it down before I leave the house, the beers clinking in a carrier bag.

For some reason, as I walk the short and familiar route to Jamie’s, I’m nervous. There’s a knot in my stomach like I used to get before kick-offs. It’s half excitement and half dead-weight, and it pulls me down and makes me want to turn around, go home and just curl up on the sofa all evening watching chat shows and online videos.

I make a list in my head of people who are likely to be there, and it’s mostly people I know – or knew – quite well. There’s not been much change in the social groups at school for years now, and everyone pretty much still hangs around with the people they’ve always hung around with. Even so, having to have the same ‘how are you’ conversation a dozen times this evening isn’t filling me with much joy. Maybe they’ll just leave me alone like they always do.

Grow

Grow