- Home

- Luke Palmer

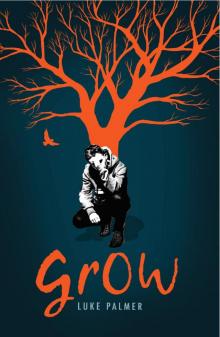

Grow

Grow Read online

Contents

Praise

About the Author

Title Page

Intoroduction

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EITHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

THIRTY-NINE

FORTY

FORTY-ONE

FORTY-TWO

FORTY-THREE

FORTY-FOUR

FORTY-FIVE

FORTY-SIX

FORTY-SEVEN

FORTY-EIGHT

FORTY-NINE

FIFTY

FIFTY-ONE

FIFTY-TWO

FIFTY-THREE

FIFTY-FOUR

FIFTY-FIVE

FIFTY-SIX

FIFTY-SEVEN

FIFTY-EIGHT

FIFTY-NINE

SIXTY

SIXTY-ONE

SIXTY-TWO

SIXTY-THREE

SIXTY-FOUR

SIXTY-FIVE

SIXTY-SIX

SIXTY-SEVEN

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CLIMATE EMERGENCY

Copyright

This book broke my heart and challenged me in so many ways … the rawest representation of how easy it is for a teenager to become stuck in a spiral and slip through the threads of society without anyone realising before it’s too late.

Ashling Brown, Netgalley

‘When an author is able to make you stop reading because it is uncomfortable, you know they have done something right … Needs to be read by many people far and wide, of any age, because anger and hate can grow from a feeling of not being seen. I applaud the author.

Robyn Spacey, The Book Club Blog

A really compelling but difficult read … the phrase emotional rollercoaster never felt so apt. With themes of grief, loss, mental health, racism and pressure as well as thought-provoking social commentary, it’s one that should have a place in every secondary school library.

Rachel Bellis, Netgalley

‘This book left me emotionally raw … ultimately I think it is a must read about racism and extremism told from an unexpected perspective.’

Vicky Bishop

Luke Palmer is a poet, author and secondary school teacher. He lives in Wiltshire with his young family. Grow is his first novel.

For H

like sparks & shining dragons

There won’t be any explosions in this book.

Sorry if that’s going to be a problem. And, while we’re at it, there won’t be any chasing around at night, or encounters with the undead, or werewolves, or vampires or anything of that kind either.

Sorry.

A few years ago, I loved those kinds of books. I’d imagine myself in a world where all the adults were dead, or gone, or both. I think I’d have been OK. Maybe not the leader of one of the rebel gangs that stalked through the abandoned streets, shouting orders that various underlings followed with glee. It wouldn’t have been me that was surrounded by hard-faced kids in ragged clothes. But I’d definitely be surviving, a sharpened stick in one hand, straddling a bike kitted out like a tank, ready to dash back to my stash of pilfered tins in the belly of an old barge down on the canal. I used to love imagining myself in those situations.

But I grew out of them.

I don’t know why I liked them, really. It’s pretty grim stuff, imagining your parents are dead. And enjoying it. This book won’t be like those books.

It will be real.

It won’t be about the future, or the past, or a world where the superpowers have gone crazy and bombed everyone back to the stone age.

You don’t need all that to create terror.

ONE

Mum burns the toast, again. The blare of the fire alarm cuts through my dream and has me on my feet in seconds, waving a pillow at the flashing plastic disc on the landing outside my room. It takes a few more painful moments to clear the sensor.

‘Sorry, love. Would you like some?’ Mum’s head appears around the banister. There are big red circles under her eyes. The fire alarm’s light carries on flashing for a while after the sound stops and it feels like there’s a place in my ears where it’s still echoing.

‘Please,’ I croak, suddenly aware of myself standing in a pair of grotty boxer shorts. I’ve passed the age when it’s OK for your mum to see you in your pants.

I have a quick shower and put my uniform on, lug my backpack downstairs and sit at the table. Mum smiles and pushes a plate towards me, and a mug of tea. Despite having burned the last round – hers – the toast is cold. The tea’s not much warmer. I wonder how long she’s been up, waiting for me.

She leans back against the counter, her dressing gown coming apart a bit at her neck. I stare at my plate, pick up crumbs that have spilled over the edge with the end of my finger. Neither of us speak. A few times she looks like she might be about to say something, ask me about what I’ll be doing today, how my friends are getting on, whether I’ve done all my homework. But she doesn’t.

It didn’t used to be like this. Mornings used to be full of noise and energy and lost keys and the cats needing feeding and making sure I had my lunch and have I got my bus card and where did I leave that folder and when’ll you be home this evening.

But not anymore.

After a few minutes Mum turns away, starts opening and closing cupboards and making scribbled notes on a pad we keep stuck to the front of the fridge. It’s Thursday, the day of the big shop, which means she’ll be late home.

I finish eating and go back upstairs to clean my teeth. The fire alarm still blinks at me on the landing. I keep the tap running, rinsing my mouth a few times to get the gritty, burnt crumbs out. They get stuck and turn into doughy sludge.

On my way out of the house, Mum stops me in the hallway and puts her hand on my cheek – just holds it there and looks at me. She’s been doing this a lot recently. I think it’s because my eyes are the same level as hers now. I smile. She does too. And then I walk through the door.

It is one of those frosty, late-autumn mornings where it hurts a bit to breathe. I push my hands deep into the pockets of my coat and pull the collar right up over my chin, the zip between my teeth. The zip has a sharp, metallic taste. Like blood. You can tell it will be a sunny day later; the cloud, or mist, or whatever it is, seems to stop not far overhead, and there are definitely some blue bits on the other side of it.

It was on a day like this, a Monday morning in October just over two years ago, that I heard Mum shout my name as I walked down the street. I had run back to her as fast as I could, shrugging my bag off my shoulders as I went. There was something in her voice that sounded like I had to, as if Mum were hidden inside her own body and was shouting at me to get her out. When I got to her, she looked at me as if she wasn’t looking at me. She had the phone clenched to her chest.

After a while, she was able to tell me.

There had been an explosion. In London.

Dad was dead.

TWO

So I lied about the explosions.

Sorry.

The Sunday evening before that phone call – before our lives were taken away from us, skinned alive, cut in half, tossed into the corner and stamped on – we’d all been sitting at the kitchen table. Dad was about to leave to catch the train into London. He worked in our town, on a leafy, high-tech business park doing something I never asked about. I regret that now – among other things. But he went into the capital regularly to meet clients or try to pick up new ones for whatever it was he did. This particular Sunday had been bright and unseasonably warm, and Dad kept finding reasons not to leave. He’d spent most of the day in the garden.

‘Sunny again tomorrow, Josh. What do you say we both ditch work? We’ve got gutters that need clearing, leaves to sweep, and the last of those plants could do with a—’

Mum interrupted our fantasy while still tapping away on her laptop, reminded me that I had a science test the next day, reminded Dad he’d been preparing for this meeting all last week.

‘But you don’t mind skipping that, Josh?’

‘Not at all, Dad. The house is a much more urgent priority, wouldn’t you say?’

‘That’s exactly what I say, Josh. But your mother…’

Mum gave us both one of her looks.

‘Ergh. London!’ Dad’s head clunked as it hit the table. One of the cats pawed at his leg.

I smiled, thumbed my phone, copied the address of a website, hit send. Dad looked down as his pocket buzzed, grinned at the screen, gave me a covert thumbs up.

Then he’d grabbed his panier bag, put his bike helmet on, and left.

Later that night, I’d received a picture message of his finger poised above a ‘book now’ button on his laptop screen – the website of a holiday company that I’d sent him the link to earlier.

I don’t know if he’d really booked that holiday or not. One of the things that got lost in the time afterwards. What I do know is, on that last Sunday evening, I’d gone to sleep in a state of happiness I didn’t realise I’d had.

Until afterwards. Until it was gone.

Dad had been on his way to that meeting when his train exploded.

Or rather, it had been exploded.

A young guy with a backpack had got on at Dad’s station, stood in the middle of the carriage, swaying with the other commuters for a few minutes. Then his backpack blew up.

They said that Dad was near the centre of the blast and would have been killed instantly.

We were supposed to see this as a kind of bonus, I think.

Some weren’t killed so instantly. One woman took a week to die.

THREE

There was a service at Westminster Abbey for all the victims’ families. Some important people talked about sacrifices and how they won’t be forgotten. We sat right at the front, just behind the important people who kept getting up to make speeches.

All the way through I couldn’t stop thinking about Greek theatre. Mrs Dinet, our drama teacher, had told us that if one of the characters in ancient Greek theatre died, they wouldn’t perform it on stage. The death would take place off stage and someone would describe it to the audience. Then, to prove that it was true, they’d part some curtains at the back of the stage, or bring in some kind of trolley on wheels, and reveal the body. Sometimes they’d use animal blood or intestines to make the death look realistic. Especially if it was a violent one.

All the way through that service I wondered whether they were going to open a curtain or roll out a trolley. I couldn’t decide whether I wanted them to or not.

How do you show someone who’s had a bomb rip through them?

The papers were all saying how it could have been worse. There was only one bomb, but they’d planned another one. The other bomber was left paralysed after his bomb didn’t go off properly and the detonation blast took a chunk out of his spine. His trial was very public. And quick. This was supposed to show our efficient justice system and our intolerance of acts of terror against our way of life.

A few weeks later, the train line re-opened. This was supposed to be an act of defiance against the people who killed my dad.

There were a lot of things that were supposed to be.

If you ask me, Dad being killed wasn’t one of them.

There were thirty-nine families in that service. Thirty-nine things that weren’t supposed to be.

Thirty-nine trolleys.

All this was just over two years ago. About the time when I stopped reading books about the end of the world, and all the adults dying.

FOUR

I get to school just as the first bell goes. I am neither the first nor the last into my lesson. Things are easier that way, I’ve noticed. You can flow in with the others and don’t have to say anything when the teacher says ‘Good Morning’. They all do this nowadays, stand in the doorway and say ‘good morning’, or ‘how are you?’ or ‘ready to get going?’ one foot inside the door, one inside the classroom. Mostly, after they’ve done this, they go back to the front of the room and talk to us like they always have done; like we’re all the same. This is fine with me. When they do their politeness thing, trying to treat us like people, there are only a few of them that I actually believe. Most of them sound totally fake.

I’m not sure about Mr Walters, whose Biology class is the first lesson today.

After a whole morning, nearly two hours of cellular differences between plants and animals, he calls me over as I’m about to leave.

‘Josh, a quick word, please?’ It sounds like a question, but it isn’t. That’s another thing they all do.

A few other pupils look at me as they walk past. I stand by his desk, watching the side of his face as he scrolls through something on his computer. His rimless glasses reflect a blue-green light from the screen.

‘Ah, here it is. Last week’s test. Josh, I was very impressed with your result.’

He waits for a reaction. I nod.

‘Almost full marks. Almost.’ He winks a bit at this. ‘Now some of that paper I took from the A-Level syllabus. Not much, but enough to push a few of you. Sort the wheat from the chaff as it were. And you, Josh, are definitely wheat.’

I smile a bit.

‘I just wanted to say how well you’re doing, Josh. Are we challenging you enough in these lessons? I know it can seem a bit slow sometimes. I’ve got to make sure everyone’s on board.’

I shake my head. ‘It’s fine.’

‘You’re sure? Good. You will let me know if we’re not pushing you enough though?’

I’m never sure what teachers expect when they ask this. I smile again.

‘Good. It sounds to me like you’re doing brilliantly everywhere, Josh. Hard to imagine it’s been…’ He slows down, looks at me closely.

I feel myself getting hot, a high-pitched ringing starts in my ears.

‘Never mind. Sorry, Josh.’ He pauses for a few seconds, then says it. ‘He’d have been proud of you, you know.’

And I leave, quickly, my ears ringing.

Mr Walters is the only one who ever mentions Dad. The first time he did it was a few months after it happened. I was in a revision class after school, catching up on the work I’d missed. Mr Walters was reading a news website. He didn’t realise the projector was still on, beaming everything he was reading up onto the whiteboard. He was looking at pictures of the bombing, and people in orange jump suits, and people sitting in front of black flags. He kept tutting and sighing, rearranging himself in his chair. It must have been during the trial. Mum and I had been trying hard to avoid the coverage as much as we could, but the news had been pretty full of those kinds of pictures for ages. Even before the London attack, there were bombs in other countries and reports of ‘constant threat’.

Dad used to say it was ridiculous fearmongering.

Mr Walters had looked over and seen my eyes on the screen, then realised. ‘I’m sorry, Josh. I forgot you were here,’ he’d said, picking up his remote control.

FIVE

The house is empty when I get home. I drop my keys on the shelf by the door and kick off my school shoes.

Sometimes I still expect the cats to greet me, but they were shipped off to live with someone else a couple of months after the explosion. Someone from the Cat’s Protection League came round while I was at school. Mum told me when I got home. To be fair, they were getting pretty mangy, and one or both of us kept forgetting to feed them or let them out. The empty spaces on the kitchen floor where the bowls used to be still trigger an ache somewhere deep in my gut – a kind of guilt that we didn’t do right by them. Mum says that she could smell the difference after the first few days.

I turn the radio on in the kitchen so the house doesn’t sound so empty, then go and get changed upstairs. Mum has a thing about being in school uniform in the evenings. She says it’s good to come home and ‘peel off the day’. She still holds me to some standards at least. This done, and with my homework spread out on the kitchen table, I fall into the rhythm of quadratic equations, and lose track of time.

The cats were all Dad’s idea. He and Mum got a pair of kittens a few years after they got married. They called them Salt and Pepper, which is about as generic as you can get. Dad always used to joke this was on purpose, that it was part of ‘what you’re supposed to do’.

It’s not as if the cats ever got called by their real names anyway. Dad always called them Bowie and Robert Smith after a couple of musicians that he’d liked back in the 1980s. He’d play me their music sometimes – old records, big black discs that shimmered in the light like oil – insisting that I listened for the moment before the needle touched the vinyl. He said you could hear something in that moment, something like suspense. A magic moment, where waiting and what you were waiting for happened at the same time.

Mum called them Ratchet and Mother, because – she said – they made her feel trapped and tied to the house ‘like a skeleton in the basement’. I don’t know what she meant.

Grow

Grow